It seems that my (enable sarcasm) favorite internet bird trainers (sarcasm off … for now) have discovered two new and powerful techniques that we professionals have been hiding because we purposely use words they can’t understand, or more accurately that they claim the average parrot owner doesn’t understand. While this new “secret” is flawed on so many levels it does inspire me to write about variable reinforcement and jackpots, the two techniques revealed.

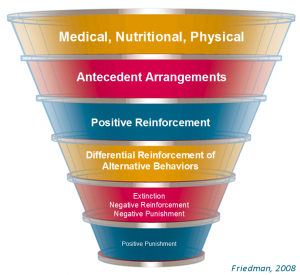

Before addressing the two techniques I want to speak to the claim that those of us who promote a science based approach to training do so by presenting complex and hard to understand terms. In fact what we present and promote is an almost profoundly simple foundation technique that goes by the name of functional analysis. I know it starts to sound like “they” are correct, it sounds really complicated. In truth it is quite simple, I agree that initially some of the terms may sound complicated but their meanings are clear. And that is the point really; behavior science enables trainers of all skill levels to communicate clearly using a common language. To learn more about this read my article “ABCs … a Training Tool“on the subject and also the articles that are referenced in it and discover the power of these techniques that have been researched and proven during the more than 100 year history of behavior science. These are not flashy phrases unique to one marketing focused outlet; they are the language of training spoken by true professionals in the human behavior science and animal training fields.

It never ceases to amuse me how these internet gurus have these mystery friends who stay in the shadows while feeding these illustrious trainers with all the secrets that the professionals don’t want you to know. This is in stark contrast to the true professionals who openly credit their sources; did I mention Dr Susan Friedman yet? Oh I guess not … but if I write about something that she taught me or that I read in one of her articles I promise I will. Anyway, back to a new strategy that is going to really change the way you train your birds … or maybe not. It is a new strategy that our gurus learned from a mystery marine mammal trainer. This new strategy is called “Random Rewards” and is the” rolls-off-your-tongue”, only used in one place name (we are told) for a technique called Variable Ratio Reinforcement Variety (VRRV) promoted by Sea World in several articles published online some time ago. The first mistake that our gurus make here is that there is nothing “random” about VRRV. There are a few variations of variable reinforcement strategies that have been studied and documented by behavior science however none of them have anything random about them at all. The second point is actually more important than a continuing misunderstanding and misrepresentation of the science and that is that for companion bird owners the best strategy is to use a one-to-one ratio of behavior to reinforcement. I say this because the strength of a behavior is directly related to the reinforcement it earns. Plus, why would you not reinforce the desired behavior? It is true that professional trainers sometimes “thin” the ratio of reinforcement as a means of getting a few more behavior repetitions in a session from an animal. However, I see no reason for a companion bird owner to need to do this and in doing so risk the behavior breaking down through poor execution of the reinforcement thinning.

The second strategy is the concept of the jackpot reinforcement and to my knowledge there is to date no solid research to support the assertion that jackpots are any more effective that “regular” reinforcement. There is certainly a belief by many animal trainers that jackpot reinforcement somehow strengthens the behavior it follows however, to date, there is no conclusive evidence or scientific study that supports this. Hopefully someday a researcher will get a research grant that permits this hypothesis to be tested rigorously in a scientific manner. Since we are talking science here I should clarify that “jackpot” in this context refers to the magnitude of the reinforcer being given. For example if you are delivering a small chip of almond as a reinforcer for a behavior and your bird does a really wonderful repetition of that behavior and you then give it half an almond, that is what is called a jackpot. It is said to be a “magnitude” reinforcer. Now, if instead of giving the bird half an almond you gave it a chip of its very favorite food, say a walnut, I suspect that would have an effect upon the future strength of the behavior, however this is not the generally accepted meaning of a jackpot.

So, once again the hype of newly invented or discovered strategies is really just reinvention, misunderstanding, and misrepresentation of the facts. The real principles of behavior and training are not difficult to understand and they are a common language for training professionals and companion animal owners alike. They are certainly not marketing hooks used only by the owners of the “secret sauce.”

If you would like your bird club or society to learn more aboout the ethical application of behavior science to bird training consider an introductory presentation. Take a look at my Behavior and Training web site for more information of write to me using the “speaking engagements” link at the top right of the page.

Sid.