You read it all the time in internet chat groups and even magazine articles, “I need urgent help with my phobic (insert parrots species).” It seems to me that the majority of people asking these questions and many of those answering them do not understand what phobia is.

Let’s start by going to Webster’s for a definition of phobia:

“Noun: an exaggerated usually inexplicable and illogical fear of a particular object, class of objects, or situation.”

I feel that it is highly unlikely that most so-called “phobic” birds have the above described type of fear. The key words here are “inexplicable” and “illogical.” The root cause of such behavior can usually be traced to the history of interactions with the owner or in the case of a rehomed bird, the previous owner(s). This is hardly “inexplicable” or “illogical”. A bird that displays aggressive behavior towards hands is probably a bird that has never been “listened to” when it clearly communicated that the hand approaching was not welcome. Through its body language a bird communicates it is either ready or not to accept an approaching hand. When the owner sees, understands, and respects this communication the bird gains a little more control over its environment and with control comes confidence.

In addition using “phobic” to describe the behavior of a bird is applying what is defined in psychology as a construct or label. Regardless of whether the condition is based upon an illogical or inexplicable fear the word “phobia” only attempts to ascribe a condition or state to the bird, it does nothing to describe what the bird actually does, or the conditions in which it does it. Remember, the smallest meaningful unit of analysis is behavior and conditions.

The first step in addressing behavioral problems is to accurately describe the behavior, what happens immediately before the behavior (the antecedent), and what immediately follows the behavior that is maintaining it (the consequence). This is what is called a functional analysis of the problem and I wrote about this process in an earlier article. That article and another describing the basic terms of the science of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) should help those looking to address fear issues.

It is also important to note that fear behaviors may “appear” to be irrational and therefore phobic because the fear-eliciting stimulus appears harmless to the trainer. However these fear behaviors are not irrational from the perspective of how they come about, which is the process of Respondent Conditioning (to be discussed in a future article).

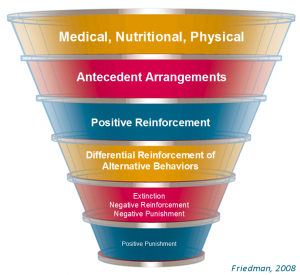

One final point, when trying to address unwanted behavior it is important to focus on what we would like the bird to do instead. Training a bird “what to do” is easier and less intrusive than trying to train it “what not to do.” The latter on its own implies the use of punishment (the reduction of a behavior) and aversives (things a bird will work to avoid). Both of these are things we try to avoid in training plans whenever possible. Training a bird “what to do” involves reinforcing desired behavior, the technique upon which we try to focus. As we build the reinforcement history of the desired behavior and at the same time attempt to avoid reinforcing the unwanted behavior we will tip the balance towards the bird offering the wanted behavior.

Sid.